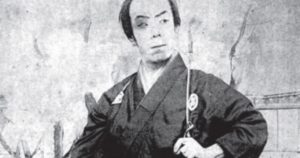

The first superstar of Japanese Cinema Matsunosuke Onoe whose life was like a earth without gravity !

Onoe was initially an actor with an itinerant kabuki troupe. In his autobiography, he claimed that he had made his stage debut as early as 1880, in a performance given by the Tamizo Onoe company.

Fascinated by the stage, he left his home by the age of 14 to travel with a troupe, and by 1892, he was acting under the stage name Tsurusaburo Onoe. In 1905, he adopted the more prestigious name Matsunosuke Onoe

His troupe regularly performed at a theater in Kyoto owned by Shozo Makino, and as a kabuki actor, he was known for his extravagant stage tricks.

In 1909, Makino was approached by Yokata Shokai, a film import and exhibition company, to produce movies, and he began to film scenes from the theater’s performances. Onoe made his movie debut in Goban Tadanobu (Tadanobu the Fox, drawn from the famous kabuki play Yoshitsune Sembon Zakura that year. Onoe’s troupe proved consistently popular, and Makino chose Onoe to star in his future movies.

Onoe starred in hundreds of films ,the 1925 Araki Mataemon was advertised as his 1,000th film. He played the lead characters in almost all dramatizations of stories published by Tachikawa Bunko, which at the time was a best-selling publisher.

He and his troupe also remained closely associated with Makino for over a decade, and Makino directed Onoe in 60 to 80 films per year, ultimately accounting for about half Onoe’s total output.

In addition to films based on kabuki, he and Makino pioneered the jidai geki (historical film) genre. Onoe also popularized the subgenre of ninja films.

Onoe’s films were well-received, earning him the affectionate nickname “Medama no Matchan” (“Eyeballs” Matsu), after his large eyes. He was especially popular among children, who took to imitating his ninja performances in their games. Many film historians consider him the first superstar of Japanese cinema because of his prolific output and his constant popularity

His films were silent, voiced-over by a live narrator (benshi) in the theaters. They largely followed the conventions of kabuki theater; for example, except for those made during the last years of his career, his movies featured male Oyama actors in the female roles.

Many of his films were shot at 8 frames per second, rather than the Western convention of 16 that was promoted by some Japanese modernizers, in order to save on film stock. Some critics have pointed to this economization, as well as to such elements as overexposure of some films causing the actors’ facial features to wash out, as evidence of primitive film-making.