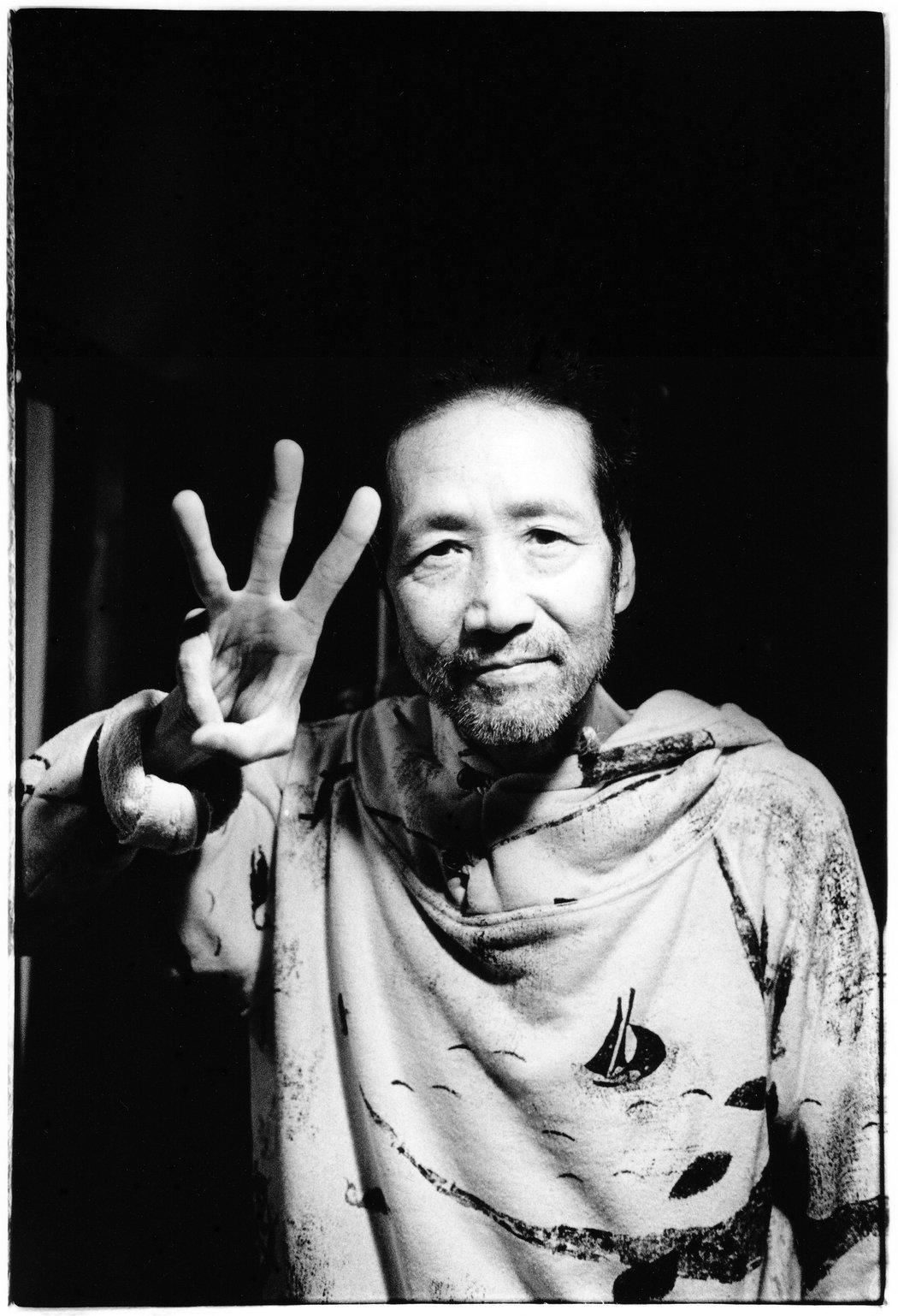

Keiichi Suzuki of Hachimitsu Pie in his hometown Ota-ku, a ward in Tokyo. His music is included in a new set of Japanese recordings from the late 1960s and early 1970s. Credit Hiroyuki Ito for The New York Times

When the Japanese singer-songwriter Kenji Endo first heard Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” as a young student in Tokyo in the 1960s, he was perplexed — offended, even. Aren’t pop vocals supposed to be pretty? But by the third listen, Mr. Endo remembered that he was in awe: “This guy is creating something that has never been created before.” He had found his calling.

And what about Mr. Dylan’s lyrics? “I had no idea what the hell he was singing about,” Mr. Endo said in a recent Skype interview.

His experience was, in one sense, a typical story of rock ’n’ roll inspiration in the 1960s. Yet it is also a window into a vital period of Japanese musical history that is only now getting a close look in the West, through a series of archival albums that document some of the innovative work that has developed along the fringes of Japan’s tightly controlled pop industry.

“Even a Tree Can Shed Tears: Japanese Folk & Rock 1969-1973,” released this month by the eclectic American label Light in the Attic, is a primer on how Japanese musicians absorbed the influence of Mr. Dylan, the Band and Joni Mitchell, as well as a portrait of a postwar generation that explored its own identity through an imported sound.

Aside from Happy End, the groundbreaking band that had a song on the “Lost in Translation” soundtrack in 2003, most of the figures in Light in the Attic’s new Japan Archival Series have never had their music released in the West before.

But for years an avid collector community has been circulating their work and gathering string on the cast of characters: the enigmatic, smoky-voiced Maki Asakawa; Hachimitsu Pie, whose name (which means “honey pie”) was a bilingual nod to the Beatles; and Sachiko Kanenobu, a songbird who ended up in Philip K. Dick’s circle in California. After “Even a Tree Can Shed Tears,” Light in the Attic plans further volumes focusing on ambient music and the 1980s genre known as city pop.

“It’s an entire kingdom of music,” said Devendra Banhart, one of the handful of Westerners who has championed these artists.

Light in the Attic, which specializes in deeply researched reissues of offbeat material — like Rodriguez, the songwriter at the center of the Oscar-winning documentary “Searching for Sugar Man” — is hoping to find an audience of open-minded listeners by wrapping the music in explanatory context. For American indie-rock fans whose exposure to Japan began with noisy exports like the Boredoms, it may be a totally new territory to explore.

The history can be traced to the aftermath of World War II, when occupied Japan was drenched in American pop culture, and a generation was reared on the jazz and rock ’n’ roll broadcast by the American military.

“I grew up with American culture,” Haruomi Hosono, a founder of Happy End and one of the architects of modern Japanese pop, said in an interview at the Red Bull Music Academy in Tokyo in 2014. “I even regretted that I wasn’t American.”

In the 1960s, collegiate folkies and Beatles-inspired guitar bands swept the country. But by the end of the decade, a circle of ambitious songwriters who were obsessed with American roots music started to emerge. Many were associated with a small record label, URC, that evaded the Japanese music industry’s strict censorship rules by selling records through the mail.

On its surface, much of “Even a Tree Can Shed Tears” can seem like an uncanny simulacrum of vintage Californian folk-rock, an alternate universe in which Buffalo Springfield and the Grateful Dead sprouted in Tokyo. But the album also shows the musicians’ efforts to forge a new kind of Japanese rock even while borrowing so heavily from the West.

Keiichi Suzuki, of Hachimitsu Pie and the long-running band Moonriders, remembers struggling to roll his tongue in an effort to make Japanese lyrics sound like English, a method that he said had been perfected by Eiichi Ohtaki of Happy End.

“While we were performing together onstage once, Mr. Ohtaki asked me, ‘Why are you singing in such a weird way?’” recalled Mr. Suzuki, who proudly wore a Devo T-shirt. “I replied, ‘I’m just imitating you.’”

Happy End transformed the rock scene with poetic Japanese lyrics that somehow fit the cadence and rhythms of American-style rock. The band’s 1971 album “Kazemachi Roman,” a classic of the genre, describes with a shrug how the Tokyo of their childhood was being swept away and replaced by a high-tech metropolis. The song “Natsu Nandesu (It’s Summer),” with echoes of Neil Young, is a wistful idyll darkened by storm clouds and a disaffected narrator: “I’m so bored, I twirl a parasol.”

Mr. Endo’s “Curry Rice” shows how some songs wedged political hot topics into scenes of everyday life. The aroma of curry on the stove fills a small apartment while the TV carries a news report about the death of Yukio Mishima, a literary star who shocked the nation by staging a failed coup and committing ritual suicide. The juxtaposition of death and hunger Mr. Endo felt in that moment, he explained, led to a “mysterious” feeling and then to an understanding of “what it means to be human.” (On Oct. 25, after this article had gone to press, Mr. Endo died at age 70. According to a note on his website, he had been suffering from stomach cancer.)

On other tracks, Takuro Yoshida, from Hiroshima, plays a sunny, fast-picking tune that could almost be by Crosby, Stills & Nash. Tetsuo Saito, the “singing philosopher,” sounds like the wild man in the meditation room as he cries in Japanese: “We strip off the masks and expose all truths of society.” (Years later, Mr. Saito had a huge pop hit that began as a Minolta TV jingle.)

As Michael K. Bourdaghs, a professor of Japanese literature and culture at the University of Chicago, explained in his book “Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon: A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop,” Happy End’s embrace of Western rock led to a kind of identity crisis: What of this music was Japanese, and what was American?

“They tried to find a way out of what was really an impossible choice by trying to do a music that was neither Japanese nor American,” Professor Bourdaghs said in an interview. “What they created was sort of an artificial form of Japanese, an artificial form of America.”

That meant complex wordplay and ambiguities created through deliberate mispronunciation. Most of the band’s lyrics were by its drummer, Takashi Matsumoto, who in 1971 wrote a probing essay about being caught between a “pseudo-West” and a “sham Japan.”

The Japanese language, Mr. Endo said, was essential to capture the details of domestic life — like the kotatsu, a small heated table and blanket where families or lovers huddle.

“There’s absolutely no kotatsu in Dylan’s songs,” he said. “A girl in a miniskirt is not putting her legs inside the kotatsu. And most importantly,” Mr. Endo added, growing agitated, “cats are not sleeping inside the kotatsu in Dylan songs.”

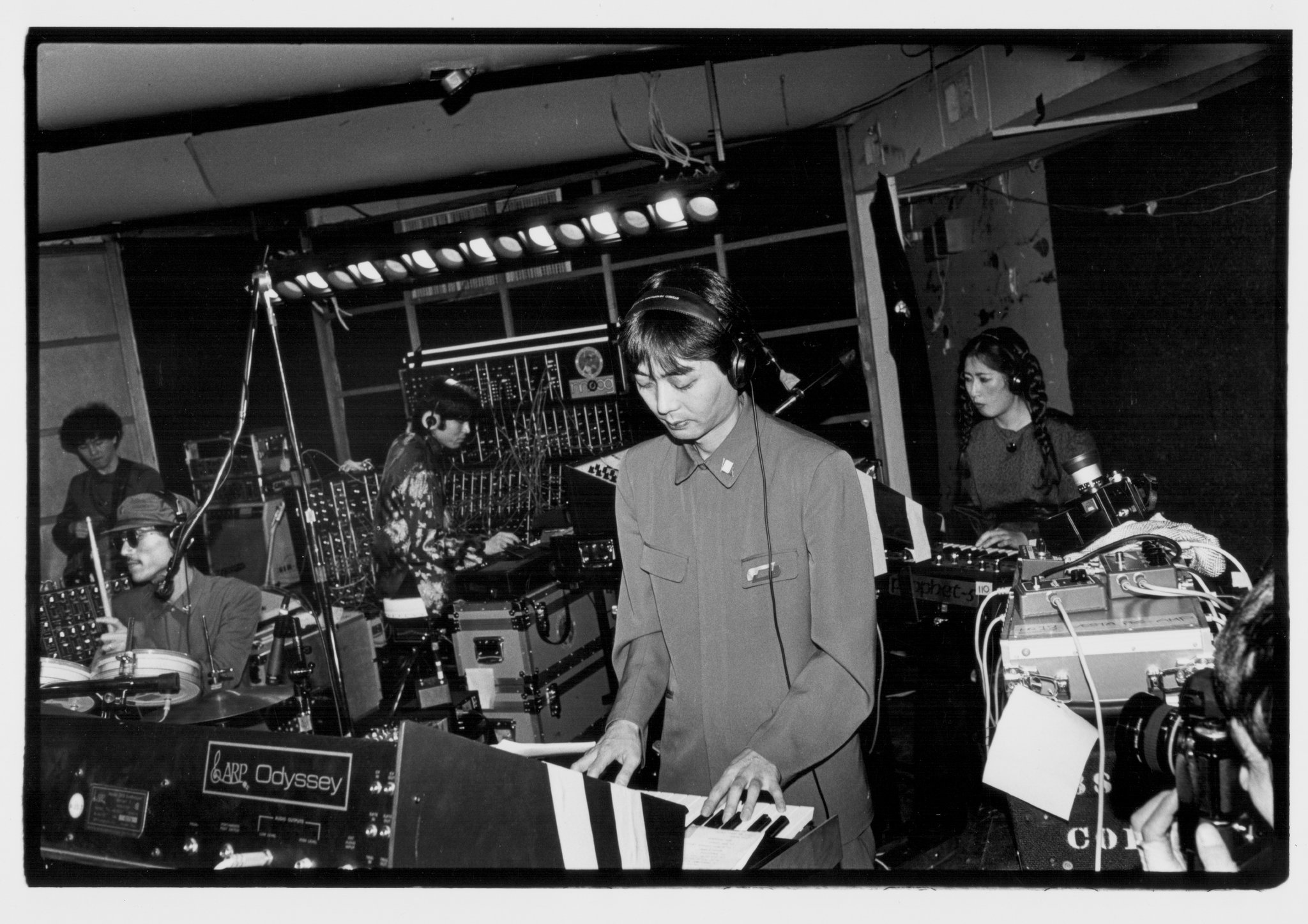

Yet language has also been a barrier keeping this music from reaching the West, said Kunihiko Murai, one of Japan’s most successful music executives. His label, Alfa, released Yellow Magic Orchestra, the techno-pop group that Mr. Hosono founded in 1978 with Ryuichi Sakamoto and Yukihiro Takahashi, which found worldwide success singing in English.

“In the ’70s and ’80s, whenever I would play Japanese songs to music publishers outside Japan, they would listen to four bars and say, ‘Nobody will listen to music with Japanese lyrics,’” Mr. Murai said. “That was the reaction in those days.”

To put “Even a Tree Can Shed Tears” together, Light in the Attic spent years trying to convince skeptical Japanese record companies that an American market existed for this material. “We were requesting something that had never been requested,” said Matt Sullivan, the label’s founder.

Light in the Attic won over the Japanese executives by stressing the label’s connoisseur approach and by projecting album sales of 3,000 — a number that astonished them, Mr. Sullivan said.

Glimpses of Japan come through in the album’s liner notes and translated lyrics. The vocal group Akai Tori sings an eerie traditional ballad about the burakumin, an ostracized social group; it was still a taboo subject, so the song was banned from the radio. Hachimitsu Pie’s “Hei No Ue De (On the Fence),” a lament with Claptonesque guitar, is about watching an ex-lover in “seven-centimeter heels” depart Tokyo’s Haneda Airport for London.

The most charming story is that of Ms. Kanenobu. In 1972 she was a 21-year-old songwriter about to release her debut album, “Misora,” when she met the American rock critic Paul Williams. Pregnant, she followed Williams back to the United States and abandoned her musical career. A decade later, Philip K. Dick, who had a long association with Williams, encouraged her to sing again.

“I met Paul in the spring of 1972, I left with him in June, and the record came out in September,” said Ms. Kanenobu, who is credited by that name on the compilation but goes by Sachiko Williams. “Now I can laugh at it. I was maybe a little cuckoo. I just followed my heart.”

The story that “Even a Tree Can Shed Tears” tells is brief, with the folk-rock scene petering out by the mid-1970s. But by then many of its players were already beginning to transform Japanese music. Mr. Hosono’s studio players became a standard backup band during the period, and later Yellow Magic Orchestra was Japan’s answer to Kraftwerk. Through the ’80s, Mr. Hosono, Mr. Ohtaki and Mr. Suzuki all wrote major pop hits.

Over his nearly 50-year career, Mr. Endo has played acoustic folk, progressive rock, techno, solo piano and sentimental ballads known as enka. And at age 70, he still looks to Mr. Dylan as an inspiration and a rival.

“I’m greater than Dylan,” he said. “The album I’m trying to make in December will be hard punk music. Dylan, can you top that?”

source-The newyork times