By Charles Q. Choi, Live Science Contributor

Pay no attention to the person wielding a samurai sword and hacking away at a pig carcass — he’s doing it for science.

The bloody exercise was done to analyze wounds from both machetes and Japanese samurai swords in order to better identify murder weapons from the cut marks they leave behind.

Lest you think the research is purely academic, it actually started during the investigation of murder cases where the victims were slain using the Japanese samurai swords known as katanas, said study lead author Penny McCardle, a consultant forensic anthropologist to the Newcastle Department of Forensic Medicine in Australia.

Because of legal concerns, McCardlecould not say too much about these cases. However, these murders occurred in the past 10 years or so, the murderers apparently used what they had at hand, and “the perpetrators were caught,” McCardle said. [See the Difference between Katana and Machete Cut Marks]

Rare and not-so-rare weapons

When McCardle began analyzing the cut marks left on the victims’ bones, she “realized very quickly that there was almost no research done on the cut marks made by katanas,” she said. “So, I started doing more research into hacking weapons in particular.”

As she researched the topic, McCardle discovered there was also very limited research describing the cut marks machetes make on bones, despite the fact that the machete “is a readily available tool throughout the world and often used in violent crime, terrorist attacks and genocide,” McCardle told Live Science. As such, she wanted to more thoroughly research the cut marks that both katanas and machetes leave behind to help archaeologists and forensic scientists better identify the kinds of weapons used against victims.

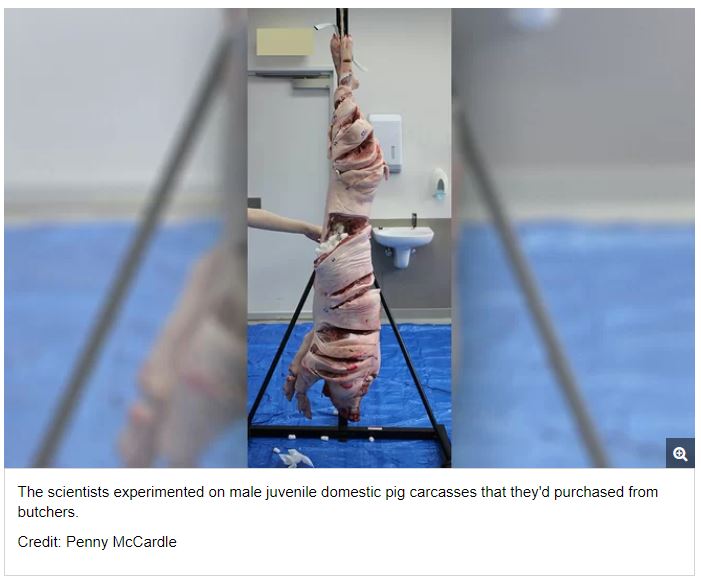

The scientists experimented on male juvenile domestic pig carcasses each weighing about 100 to 110 lbs. (45 to 50 kilograms) that were all purchased from butchers. The carcasses were filled with Styrofoam packing peanuts to keep their internal cavities stable, and were hung from metal frames to simulate standing victims.

The researchers used a factory-made machete, a factory-made katana and a katana forged using traditional methods. The volunteers wielding the machete and the factory-madekatana had no experience cutting with them and used hacking motions on carcasses, while the volunteer wielding the traditionally forged katana has 16 years of experience as a swordsman and performed expert slicing cuts, McCardle said. [In Photos: The Last Century of Samurai Swordsmen]

“The inexperienced weapon users were really surprised at how hard hacking and cutting was and how tired they got,” McCardle said. “Mind you, they did not have the adrenaline rush that I imagine people would get during an actual crime.”

Distinctive Marks

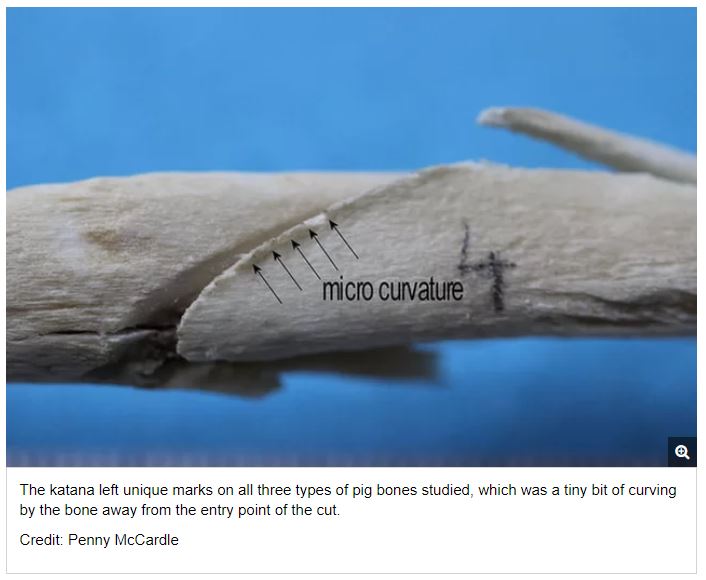

The scientists looked at the cut marks the weapons made on the ribs, flat bones such as the shoulder bone, and long bones such as limb bones. They found that a trait unique to the katana on all three bone types were tiny amounts of curving by the bone away from the entry point of the cut, while a feature unique to the machete on all three bone types was “chattering,” or the breaking off of small chips of bone at the edges of each bone.

The differences in the cut marks associated with each weapon may be due to “what the blades are made of, the way the blades are used, the angle of impact on the bone and the way the blade is removed from the bone,” McCardle said.

Future research can explore whether it is possible to deduce the experience of the sword user based on the cut mark traits, McCardle said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Feb. 21 in the Journal of Forensic Sciences.

Original article on Live Science.

Source : www.livescience.com